Downsides of Local First / Offline First

So you have read all these things about how the local-first (aka offline-first) paradigm makes it easy to create realtime web applications that even work when the user has no internet connection. But there is no free lunch. The offline first paradigm is not the perfect approach for all kinds of apps.

In the following I will point out the limitations you need to know before you decide to use RxDB or even before you decide to create an offline first application.

It only works with small datasets

Making data available offline means it must be loaded from the server and then stored at the clients device. You need to load the full dataset on the first pageload and on every ongoing load you need to download the new changes to that set. While in theory you could download in infinite amount of data, in practice you have a limit how long the user can wait before having an up-to-date state. You want to display chat messages like Whatsapp? No problem. Syncing all the messages a user could write, can be done with a few HTTP requests. Want to make a tool that displays server logs? Good luck downloading terabytes of data to the client just to search for a single string. This will not work.

Besides the network usage, there is another limit for the size of your data. In browsers you have some options for storage: Cookies, Localstorage, WebSQL and IndexedDB.

Because Cookies and Localstorage is slow and WebSQL is deprecated, you will use IndexedDB. The limit of how much data you can store in IndexedDB depends on two factors: Which browser is used and how much disc space is left on the device. You can assume that at least a couple of hundred megabytes are available at least. The maximum is potentially hundreds of gigabytes or more, but the browser implementations vary. Chrome allows the browser to use up to 60% of the total disc space per origin. Firefox allows up to 50%. But on safari you can only store up to 1GB and the browser will prompt the user on each additional 200MB increment.

The problem is, that you have no chance to really predict how much data can be stored. So you have to make assumptions that are hopefully true for all of your users. Also, you have no way to increase that space like you would add another hard drive to your backend server. Once your clients reach the limit, you likely have to rewrite big parts of your applications.

UPDATE (2023): Newer versions of browsers can store way more data, for example firefox stores up to 10% of the total disk size. For an overview about how much can be stored, read this guide

Browser storage is not really persistent

When data is stored inside IndexedDB or one of the other storage APIs, it cannot be trusted to stay there forever. Apple for example deletes the data when the website was not used in the last 7 days. The other browsers also have logic to clean up the stored data, and in the end the user itself could be the one that deletes the browsers local data.

The most common way to handle this, is to replicate everything from the backend to the client again. Of course, this does not work for state that is not stored at the backend. So if you assume you can store the users private data inside the browser in a secure way, you are wrong.

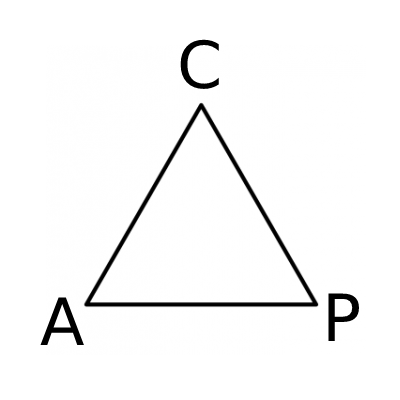

There can be conflicts

Imagine two of your users modify the same JSON document, while both are offline. After they go online again, their clients replicate the modified document to the server. Now you have two conflicting versions of the same document, and you need a way to determine how the correct new version of that document should look like. This process is called conflict resolution.

-

The default in many offline first databases is a deterministic conflict resolution strategy. Both conflicting versions of the document are kept in the storage and when you query for the document, a winner is determined by comparing the hashes of the document and only the winning document is returned. Because the comparison is deterministic, all clients and servers will always pick the same winner. This kind of resolution only works when it is not that important that one of the document changes gets dropped. Because conflicts are rare, this might be a viable solution for some use cases.

-

A better resolution can be applied by listening to the changestream of the database. The changestream emits an event each time a write happens to the database. The event contains information about the written document and also a flag if there is a conflicting version. For each event with a conflict, you fetch all versions for that document and create a new document that contains the winning state. With that you can implement pretty complex conflict resolution strategies, but you have to manually code it for each collection of documents.

-

Instead of the solving conflict once at every client, it can be made a bit easier by solely relying on the backend. This can be done when all of your clients replicate with the same single backend server. With RxDB's Graphql Replication each client side change is sent to the server where conflicts can be resolved and the winning document can be sent back to the clients.

-

Sometimes there is no way to solve a conflict with code. If your users edit text based documents or images, often only the users themselves can decide how the winning revision has to look. For these cases, you have to implement complex UI parts where the users can inspect the conflict and manage its resolution.

-

You do not have to handle conflicts if they cannot happen in the first place. You can achieve that by designing a write only database where existing documents cannot be touched. Instead of storing the current state in a single document, you store all the events that lead to the current state. Sometimes called the "everything is a delta" strategy, others would call it Event Sourcing. Like an accountant that does not need an eraser, you append all changes and afterwards aggregate the current state at the client.

// create one new document for each change to the users balance

{id: new Date().toJSON(), change: 100} // balance increased by $100

{id: new Date().toJSON(), change: -50} // balance decreased by $50

{id: new Date().toJSON(), change: 200} // balance increased by $200- There is this thing called conflict-free replicated data type, short CRDT. Using a CRDT library like automerge will magically solve all of your conflict problems. Until you use it in production where you observe that implementing CRDTs has basically the same complexity as implementing conflict resolution strategies.

Realtime is a lie

So you replicate stuff between the clients and your backend. Each change on one side directly changes the state of the other sides in realtime. But this "realtime" is not the same as in realtime computing. In the offline first world, the word realtime was introduced by firebase and is more meant as a marketing slogan than a technical description. There is an internet between your backend and your clients and everything you do on one machine takes at least once the latency until it can affect anything on the other machines. You have to keep this in mind when you develop anything where the timing is important, like a multiplayer game or a stock trading app.

Even when you run a query against the local database, there is no "real" realtime. Client side databases run on JavaScript and JavaScript runs on a single CPU that might be partially blocked because the user is running some background processes. So you can never guarantee a response deadline which violates the time constraint of realtime computing.

Eventual consistency

An offline first app does not have a single source of truth. There is a source on the backend, one on the own client, and also each other client has its own definition of truth. At the moment your user starts the app, the local state is hopefully already replicated with the backend and all other clients. But this does not have to be true, the states can have converged and you have to plan for that. The user could update a document based on wrong assumptions because it was not fully replicated at that point in time because the user is offline. A good way to handle this problem is to show the replication state in the UI and tell the user when the replication is running, stopped, paused or finished.

And some data is just too important to be "eventual consistent". Create a wire transfer in your online banking app while you are offline. You keep the smartphone laying at your night desk and when you use again in the next morning, it goes online and replicates the transaction. No thank you, do not use offline first for these kinds of things, or at least you have to display the replication state of each document in the UI.

Permissions and authentication

Every offline first app that goes beyond a prototype, does likely not have the same global state for all of its users. Each user has a different set of documents that are allowed to be replicated or seen by the user. So you need some kind of authentication and permission handling to divide the documents. The easy way is to just create one database for each user on the backend and only allow to replicate that one. Creating that many databases is not really a problem with for example CouchDB, and it makes permission handling easy. But as soon as you want to query all of your data in the backend, it will bite back. Your data is not at a single place, it is distributed between all of the user specific databases. This becomes even more complex as soon as you store information together with the documents that is not allowed to be seen by outsiders. You not only have to decide which documents to replicate, but also which fields of them.

So what you really want is a single datastore in the backend and then replicate only the allowed document parts to each of the users. This always requires you to implement your custom replication endpoint like what you do with RxDBs GraphQL Replication.

You have to migrate the client database

While developing your app, sooner or later you want to change the data layout. You want to add some new fields to documents or change the format of them. So you have to update the database schema and also migrate the stored documents. With 'normal' applications, this is already hard enough and often dangerous. You wait until midnight, stop the webserver, make a database backup, deploy the new schema and then you hope that nothing goes wrong while it updates that many documents.

With offline first applications, it is even more fun. You do not only have to migrate your local backend database, you also have to provide a migration strategy for all of these client databases out there. And you also cannot migrate everything at the same time. The clients can only migrate when the new code was updated from the appstore or the user visited your website again. This could be today or in a few weeks.

Performance is not native

When you create a web based offline first app, you cannot store data directly on the users filesystem. In fact there are many layers between your JavaScript code and the filesystem of the operation system. Let's say you insert a document in RxDB:

- You call the RxDB API to validate and store the data

- RxDB calls the underlying RxStorage, for example PouchDB.

- Pouchdb calls its underlying storage adapter

- The storage adapter calls IndexedDB

- The browser runs its internal handling of the IndexedDB API

- In most browsers IndexedDB is implemented on top of SQLite

- SQLite calls the OS to store the data in the filesystem

All these layers are abstractions. They are not build for exactly that one use case, so you lose some performance to tunnel the data through the layer itself, and you also lose some performance because the abstraction does not exactly provide the functions that are needed by the layer above and it will overfetch data.

You will not find a benchmark comparison between how many transactions per second you can run on the browser compared to a server based database. Because it makes no sense to compare them. Browsers are slower, JavaScript is slower.

Is it fast enough?

What you really care about is "Is it fast enough?". For most use cases, the answer is yes. Offline first apps are UI based and you do not need to process a million transactions per second, because your user will not click the save button that often. "Fast enough" means that the data is processed in under 16 milliseconds so that you can render the updated UI in the next frame. This is of course not true for all use cases, so you better think about the performance limit before starting with the implementation.

Nothing is predictable

You have a PostgreSQL database and run a query over 1000ths of rows, which takes 200 milliseconds. Works great, so you now want to do something similar at the client device in your offline first app. How long does it take? You cannot know because people have different devices, and even equal devices have different things running in the background that slow the CPUs. So you cannot predict performance and as described above, you cannot even predict the storage limit. So if your app does heavy data analytics, you might better run everything on the backend and just send the results to the client.

There is no relational data

I started creating RxDB many years ago and while still maintaining it, I often worked with all these other offline first databases out there. RxDB and all of these other ones, are based on some kind of document databases similar to NoSQL. Often people want to have a relational database like the SQL one they use at the backend.

So why are there no real relations in offline first databases? I could answer with these arguments like how JavaScript works better with document based data, how performance is better when having no joins or even how NoSQL queries are more composable. But the truth is, everything is NoSQL because it makes replication easy. An SQL query that mutates data in different tables based on some selects and joins, cannot be partially replicated without breaking the client. You have foreign keys that point to other rows and if these rows are not replicated yet, you have a problem. To implement a robust Sync Engine for relational data, you need some stuff like a reliable atomic clock and you have to block queries over multiple tables while a transaction replicated. Watch this guy implementing offline first replication on top of SQLite or read this discussion about implementing offline first in supabase.

So creating replication for an SQL offline first database is way more work than just adding some network protocols on top of PostgreSQL. It might not even be possible for clients that have no reliable clock.

Ask a question on the forums about Downsides of Local...

Ask a question on the forums about Downsides of Local...